When you are the daughter of a larger-than-life woman, as I am, you pay attention to women in the same shoes. When you bear the same name, the comparisons cannot be avoided. My mother, Madeline McLean Smith, lived a full and vibrant life. A kindergarten teacher for over 30 years, when she passed in 2019 the pews in the church were filled with her former students, and on the altar the priest who officiated the service was a kindergarten alumnus as well. So as I, Madeline Margaret Smith, began my volunteer stint with Linden Place, I paid special attention to the stories I heard about Ethel Barrymore Colt and her daughter Ethel Barrymore Colt Miglietta. Ethel the daughter said of Ethel her mother “She was the greatest woman I ever knew. Nine times bigger than life.”[1]

Ethel Senior was born on August 15 (my birthday as well) in 1879 in Philadelphia. She said in her memoir that on her mother’s side she came from an unbroken line of actors 1000 years long. As a young child she longed to be a concert pianist, and practiced many hours each day. Her mother Georgina became ill with tuberculosis, and the two of them moved to Santa Barbara. Sadly, after a brief time there, her mother died in 1893. Ethel, all of age 13, was in charge of packing up their belongings, including the coffin, for the long train ride back East. In 1901 her father Maurice was committed to Bellevue Hospital. Ethel paid for her father’s stay in the institution. He died in 1905.

Reading any biography of Ethel, she is most often described as “The First Lady of the American Theatre”. Her two brothers, John and Lionel also were in the family business. (John is the grandfather of actress Drew Barrymore.) Ethel was the “IT” girl of her day – gorgeous, talented, and smart. On IMDb, her stage credits run from 1895 to 1944 and include 68 appearances in Broadway shows. Add another 15 or so throughout the United States and in London. Then add movies, radio and TV. Then add the Broadway theater named for her and dedicated in 1928. Nominated for four Oscars, she won in 1945, Best Actress in a Supporting Role, for “None But the Lonely Heart”. She was a formidable woman.

In 1909 she married Russell Griswold Colt, son of Colonel Samuel Pomeroy Colt, grandson of Theodora Colt, and great-grandson of George DeWolf, who built Linden Place. There are a couple of stories of how the couple met – but this is the one I like. They were at the Hamptons, and handsome Russell strolled in and seemingly captivated Ethel. Colonel Samuel Colt, living in New York City at Holland House, saw the sparks and set up a meeting. He said to Ethel, “I can’t understand why you want to marry my son. I have no money.” Ethel’s retort, as an independent woman: “I don’t want money.” The Colonel was surprised – How are you going to live? Well, she said, “I make enough money, but I think it would be good if Russell had some kind of a job.”[2] The Colonel soon set his son up in a stock brokerage firm.

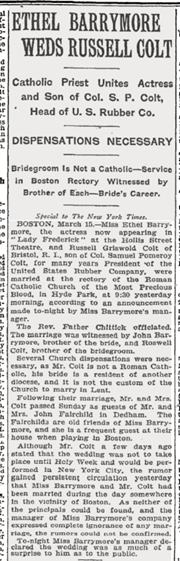

Ethel and Russell were married in the rectory of a Catholic Church. Ethel, smart and persistent, had to overcome three obstacles: first, her husband was not Catholic. So she arranged a dispensation from Bishop O’Connell – later William Henry O’Connell, Archbishop of Boston, the first to become a Cardinal. Secondly, she was not from that parish. And third, it was Lent. But Ethel persevered, and the wedding took place, with a lovely reception at a friend’s home in Dedham, Massachusetts afterwards. The couple had three children: Samuel “Sammy” Colt (1909–1986), a Hollywood agent and occasional actor; namesake Ethel Barrymore Colt (1912–1977), actress and singer; and John Drew Colt (1913–1975), who became an actor. The marriage was rocky, and in 1923 Ethel and Russell divorced. Ethel, however, stood firm in her Catholic faith (as did my mother all of her life): no alimony, no child support – “The divorce is recognized legally, but not by the church nor me.”[3]

My Mom had six children in ten years, was a devout Catholic, and stayed married even though my father struggled with alcoholism. Her hero was the Cardinal who followed O’Connell – Richard Cardinal Cushing of Boston. During her years as an educator she was a proud member of the Teachers Union, and would have approved of Ethel’s activism in the 1919 actors’ strike. Ethel became a leader of the Actors’ Equity Group, and helped end the strike that closed seven shows on Broadway. For her efforts, she was one of the five people chosen to sign the five year pact between actors and management that ended the strike. My Mom in her retirement joined with other union members and raised thousands of dollars for scholarships for students attending UMass Boston and studying to be teachers. I know first hand that she was an exceptional teacher, and my first four years in elementary school were in the same building in which she taught. All (teachers’) eyes were upon me. I was challenged – and I like to think that I overcame that burden and rose to the occasion. But daughter Ethel had it even harder.

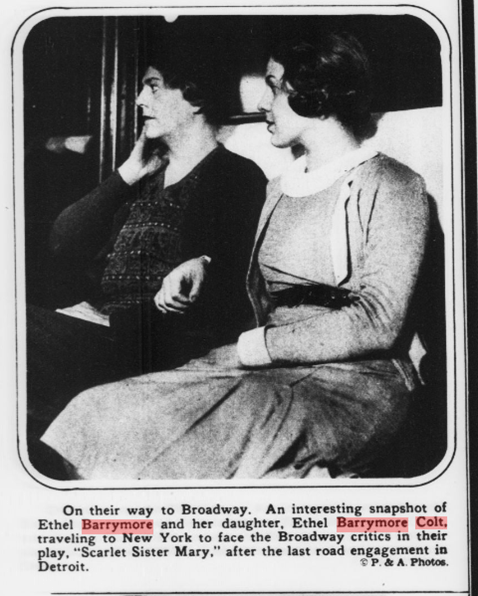

Ethel Barrymore Colt understood clearly the burden of her heritage. Her favorite quote was from Goethe: “That which thy fathers have bequeathed to thee, earn it anew if thou wouldst possess it.” I am sure she added, silently, the word mothers to that quote. She did earn it. Appearances on Broadway, on TV, with the New York City Opera Company (and eight other opera companies), hundreds of concerts, many one woman shows, tours of Europe, stints teaching theater at institutions such as the University of Alabama and Pace University, she earned her place in the theater. From her Broadway debut in 1930 with her mother in “Scarlett Sister Mary” to Harold Prince’s 1971 “Follies”, her talent was immeasurable. Born in 1912 in Mamaroneck, New York, she would travel with Ethel on the Fall River boat to Bristol for the 4th of July festivities. “Colonel Colt’s house was lovely, with a wonderfully beautiful staircase.” As a young child, the carriage rides around town must have been thrilling as well.

Ethel ‘paid her dues’ as they say in the business – for five years she owned and operated the Jitney Players, travelling 30,000 miles in a single season, in charge of everything from costume adjustments to stage preparations to driving the truck. During summers in Bristol, she ran a summer school for theater students, gave local concerts, and helped raise funds for local institutions such as the United Fund, and the Bristol Historical and Preservation Society, and the Bristol Art Museum – donating a building to house them on the grounds of Linden Place. In 1970 she was involved in founding the annual blessing of the animals at Coggleshall Farm.

Her mother made her final professional appearance in a 1957 television spectacular. Tributes poured in, including telegrams from President Harry Truman and former Prime Minister Winston Churchill (allegedly an old flame). Twenty years later, in 1977, daughter Ethel passed. At a ceremony at Roger Williams College, she was awarded an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree.

Maya Angelou once said “To describe my mother would be to write about a hurricane in its perfect power. Or the climbing, falling colors of a rainbow.” To me, thinking of my mother and the Madeline and Madeline story while discovering the story of Ethel and Ethel is like finding pots of gold at both ends of that rainbow. I am grateful for the reminder, and say in tribute:

“Here’s to strong women. May we know them. May we be them. May we raise them.”

[1] The Rhode Island State Trooper, The Great Lady of Colt State Park: Miss Ethel Barrymore, 2001

[2] Memories, An Autobiography, by Ethel Barrymore, 1956

[3] Ibid