If you grew up as a child in the 50s or 60s, as I did, it’s a wonder we are alive. Mumps. Measles. Chickenpox. If one Smith kid got it, all six got it. We played in the street unsupervised, didn’t even know what a bike helmet was, and ate dirt. No seatbelts – we sat in the way, way back of the station wagon with our noses pressed up against the rear door glass of the Olds Vista Cruiser. Same car we learned to drive on in the 70s. As a baby I was wheeled around in the “folderola”. $14.95 in 1950. Doesn’t look like the most reliable all terrain vehicle. No one measured the gap in the slats of a crib. And if you traveled and needed a baby bed, a dresser drawer would do just fine.

New father Joe Smith did his best to help out. But I am sure like many other new fathers, he found out that Mom did everything best. Whatever he did, she did over. One day, though, she needed a break – ‘please Joe, for God’s sake, take the baby with you for a ride or something so I can get a nap.’ So Dad and I went to the local Sears Roebuck. Joe could stroll the aisles and gaze longingly at all the (expensive) shiny new tools on the shelves. The urban myth goes that he came home from his Sears reverie without me. Left in the aisle with the wrenches. A hasty trip back, and there I was, sound asleep at the cash register. The sales associates did not panic, and gave the situation a little time to unfold before calling the coppers. Dad escaped Child Protective Services, but I am sure faced a worse punishment from the wife.

Part Six

Ponsonby. Unusual name. Well, in truth, if your last name is Smith anything is unusual. The Ponsonbys came to England with William the Conqueror, in 1066. They settled in Carlisle, on the northwest coast of England, facing Ireland. My great great grandparents on my mother’s side were Catherine Spillane, who married Ponsonby Chartres. Pons was born in 1840 and lived in Dublin, and in 1856 his father gave him an ultimatum: go to college, or get out. So he got out. In 1856 he sailed to Canada, lived in Toronto for a while, then went to New York City. In 1861 he went back to England – the prodigal child – to reconcile with his father. He married Catherine – “Kate” – in 1863. They had three children, and one of them, Frances Jane, born in 1867 in Brooklyn, NY, was my great-grandmother. She died in 1942, in Dorchester, MA.

Ponsonby ran a dry goods and furniture store on Fulton Street in New York. He had bad luck with a partner, who robbed him blind. He had even worse luck with his health, and died at age 36 of pneumonia, called “the captain of the men of death”. His death left Kate to fend for herself with her children. Her Aunt Mary Chartres, back in England, kept them afloat. Remember that 1929 honeymoon, the grand tour of Europe, that my grandparents took? Well, while they were there, they visited Aunt Mary at her home at Brighton Beach

Ponsonby’s brother, Archibald, wrote songs. That were actually published. Most interestingly, he had a patent for a special shoelace – a shoelace for men that had a permanent bow knot in it. Frances Jane Chartres, the youngest of Ponsonby and Kate’s children, married Charles Franklin Goodale in 1896. They met through music. He was in the church choir, St. Patrick’s of Stoneham, Massachusetts. His business brought him to Brooklyn, New York for a few months, so for diversion he decided to join a choir there. He was quite taken with the young lady who was the organist. The affection resulted in nine children, and my grandmother Madeline was the eldest, as am I.

Part Seven

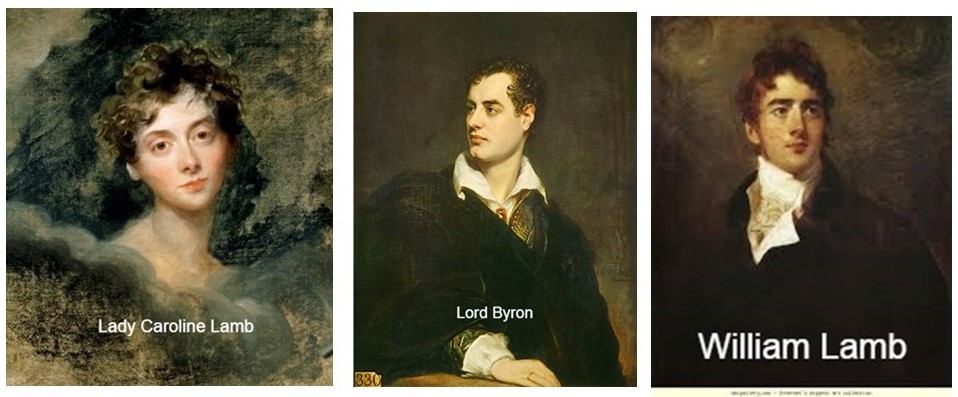

Admit it. When you learn about your family history, you want to find just one bad boy. Just one wild woman. Just one to explain why, every once in a while, you want to channel James Dean or Madonna. Well, remember Ponsonby? His third cousin once removed was a corker. A relative descended from William Ponsonby, the great literary publisher of the Elizabethan era, who brought to the world the works of Edmund Spencer. His great-grandson, the 3rd Earl of Bessborough, had a daughter – Caroline Ponsonby, born in 1785. Tomboy in her youth, beautiful all her life, given to excess, she grew up in and around the court. For some semblance of respectability, she marries the honorable William Lamb when she is 19, in 1805. So she is now Lady Caroline Lamb.

She writes “Glenarvon”, a novel published in 1816, about the Irish Rebellion of 1798.

And the hero of her novel? Inspired by Lord Byron – yup, the poet. In full dramatic fashion she writes this stirring speech to showcase her protagonist’s passion: “Arise then, united sons of Ireland – arise like a great and powerful people determined to live free or die!” Hmmm….sounds familiar. And how does the author do her research on her hero? Up close and personal.

Lady Caroline’s blood runs hot. Wanton, or witty? Eccentric, or erotic? From March to August of 1812 she and Lord Byron carried on a torrid – and public – affair that shocked London. She is 26, he is 24. She calls him “mad, bad, and dangerous to know”.

Alas, you can guess the ending – and it is not good. Lord Byron gets tired of her stalking him and dumps her, her husband separates from her and then has his own string of affairs. She dies in 1828 of a combination of alcohol and laudanum. She is 42. Byron dies in 1824. He is 36. And The Honorable William Lamb? In 1835 he ends up as the Prime Minister of Britain under Queen Victoria.

The whole story was captured in a British movie in 1972. Sarah Miles plays Caroline. Jon Finch plays William. And Richard Chamberlain, our very own leading man of “Doctor Kildare” fame, still alive at 85, plays Lord Byron.

Live free, or die !

Part Eight

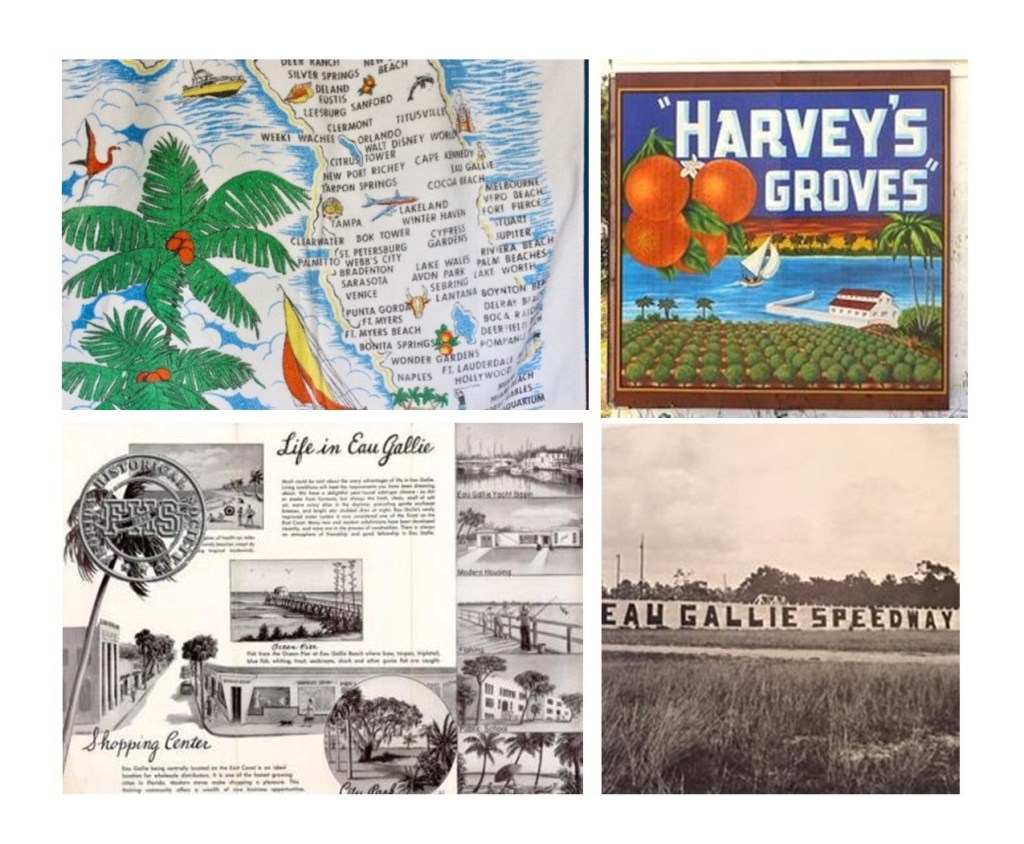

So, after our voyeur detour into the life of Lady Caroline Lamb, it’s back to the future – well, back to 1952 Eau Gallie, Florida. I have been safely rescued from the tool aisle of the local Sears Roebuck store. Hon and Dearie are happy with their newborn, and have child care support from Mrs. Jessup next door. Friends come to visit and outings to the park, or to the orange groves, or the speedway, or even all the way to Cypress Gardens fill the weekends with fun. In my mother’s treasures I find lots of letters and lots of vintage postcards. Then the Smiths discover – rather quickly after my arrival, in fact – that baby #2 is on its way. (I was born in August of 1952, baby #2 is born in December of 1953.) It’s time to pack up the Buick and head north to the extended family.

Once again Grandpa Smith comes through and helps out with the down payment on a two family house in Roslindale, a neighborhood of Boston. Very practical, with rental income from the first floor to cover the mortgage. I don’t know what the house cost in 1952, but let’s just say this rather modest home on a tiny lot was assessed for $95,000 in 1985. The 2020 assessment? $600,000.

I grew up on Orange Street – a neighborhood filled with families. Big families. 5, 6, 8 kids big. The Smiths and the Flynns and the Kellys and the Garbetts and the Giacoppos. All Catholic. All with mothers who graduated from the same maternal boot camp, and who took no guff. If Mrs. Smith wasn’t around to give you a crack when you misbehaved, Mrs. Giocoppo was. With permission. We walked to the school right around the corner on Beech Street, the Mozart, built in 1932. You know how old I am when I tell you I remember the dairy farm across the street. Whittemore Farm. I found a post on the Roslindale Historical Society Facebook page: “I worked for The Farm and was paid $1 a day to deliver milk. The Farm’s tag line? ‘You can whip our cream, but you can’t beat our milk.’ ” We lived on Orange Street until 1968, when we moved to Russett Road. No dairy farms allowed in tony West Roxbury. ❤️🐄😁 But for years and years, fresh oranges and grapefruits would arrive every winter, like clockwork, from Eau Gallie.