When I moved to Bristol, RI in 2020, I became interested in local history. This is one of the stories that was fascinating to me, and inspired deeper investigation.

My research is ongoing.

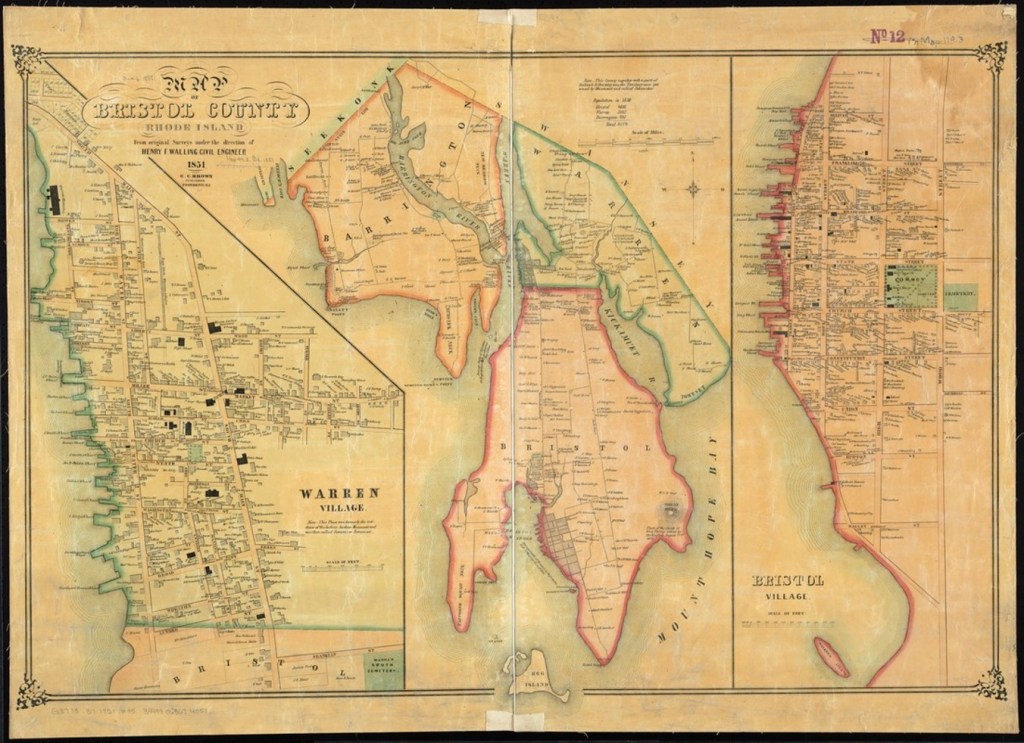

There were historical and anecdotal references to a free black community that developed in Bristol after slavery was banned, but I wanted to go beyond the oral history and find primary source evidence about the neighborhood and the people who lived there. Using the 1850 federal census, an 1851 map from the Norman Levanthal Collection, and the primary source research from the Timeline of the Enslaved, we set out to create a snapshot of one moment in time where the free black community of Bristol lived.

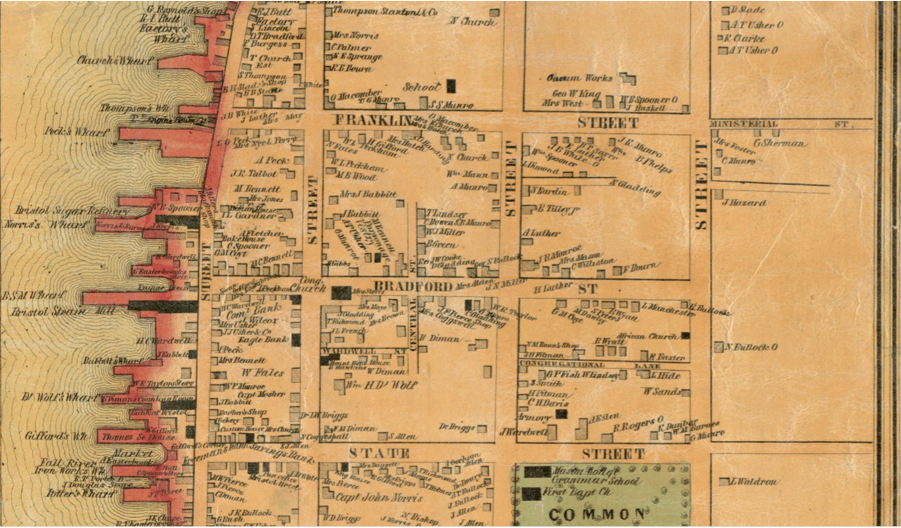

This is a map of Bristol, RI from 1851. Closer inspection of each dwelling marked on the map shows the name of the owner.

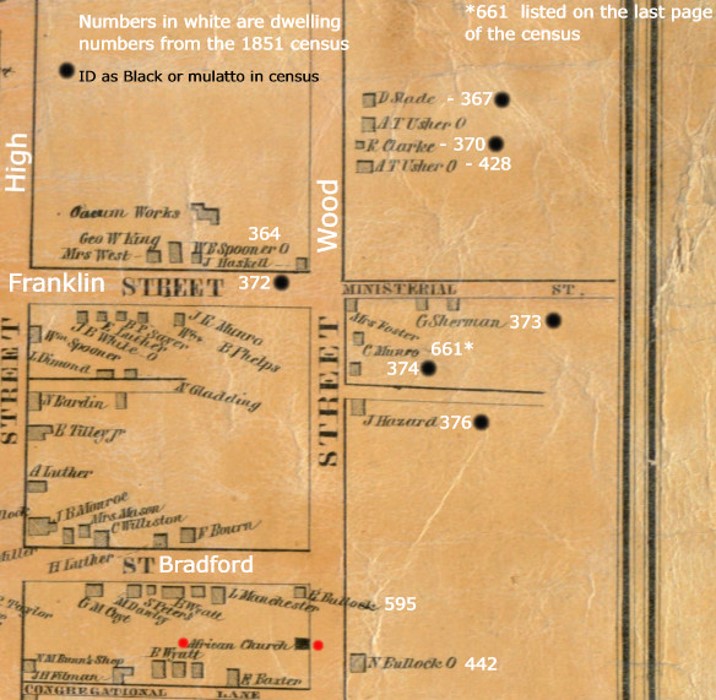

This is the 1850 Federal Census. For the first time, each person living in a household was identified by name, age, sex, color and occupation. In addition, a column marked “Value of Real Estate Owned” indicated ownership of the building by an occupant.

By crossing referencing the names on the mapped dwellings with the names in the census, those homes owned and occupied by people of color could be identified.

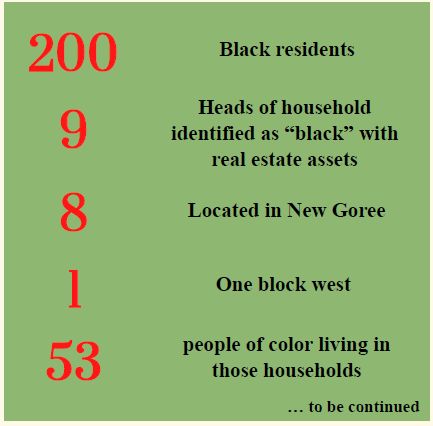

This is the simplified breakdown of the findings.

The New Goree neighborhood sits outside the Town plan. It is located along Wood Street, from Charlie Munro’s Corner north to Crooked Lane – that’s State Street to Bay View Avenue today. The neighborhood is named for Goree, from the island off Senegal. Like Little Italy or Chinatown, it denotes where a certain group of people live.

Local architectural historian Dr. Kevin Jordan has identified about 9 or 10 houses in the neighborhood as a “Goree Style” House. These Bristol houses are built using a traditional African 12 foot span, rather than the 16 foot span used by Anglo Americans. So building practices in some homes in New Goree are similar to what James Deetz discovered in the Parting Ways settlement.

Deetz’s comparison of the Turner-Burr house with a Yoruba House from West Africa, then a shotgun house in Haiti, and finally with the Anglo-American hall and parlor outline show how African cultural memory appears in these house styles. While we have no such excavations in Bristol, we do have similar 12’ measurements. There seems to be a cultural construction memory here in Bristol as well.

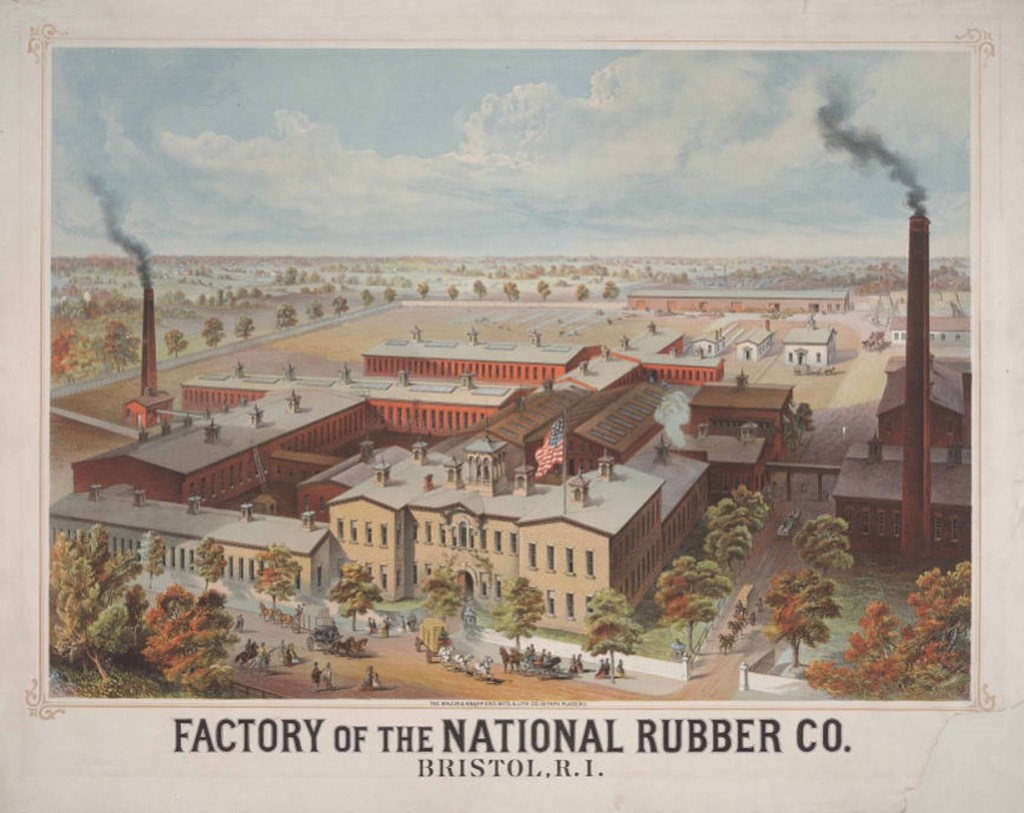

On June 24, 1865 the Bristol Phoenix reported on the opening celebration of the National Rubber Company plant – built at a cost of $110,000. Some say this was the beginning of the end of the Goree neighborhood. The Bristol company made rubberized clothing, boots, and shoes. By the 1870s many of the black residents of Goree had moved out of town – perhaps in an effort to find jobs elsewhere.

Some residents tried to co-exist with the factory. But it took determination and grit – and Marie Hazard had both – to get the better of the factory’s white owners. This is the Marie Hazard House. It is a typical small Goree house of the time; take off the embellishments and you can see the 12 foot module in the proportions. She sold her land to the National Rubber Company in exchange for two lots across the street, where she moved her house to its present location. Her son Daniel then bought it in 1875.

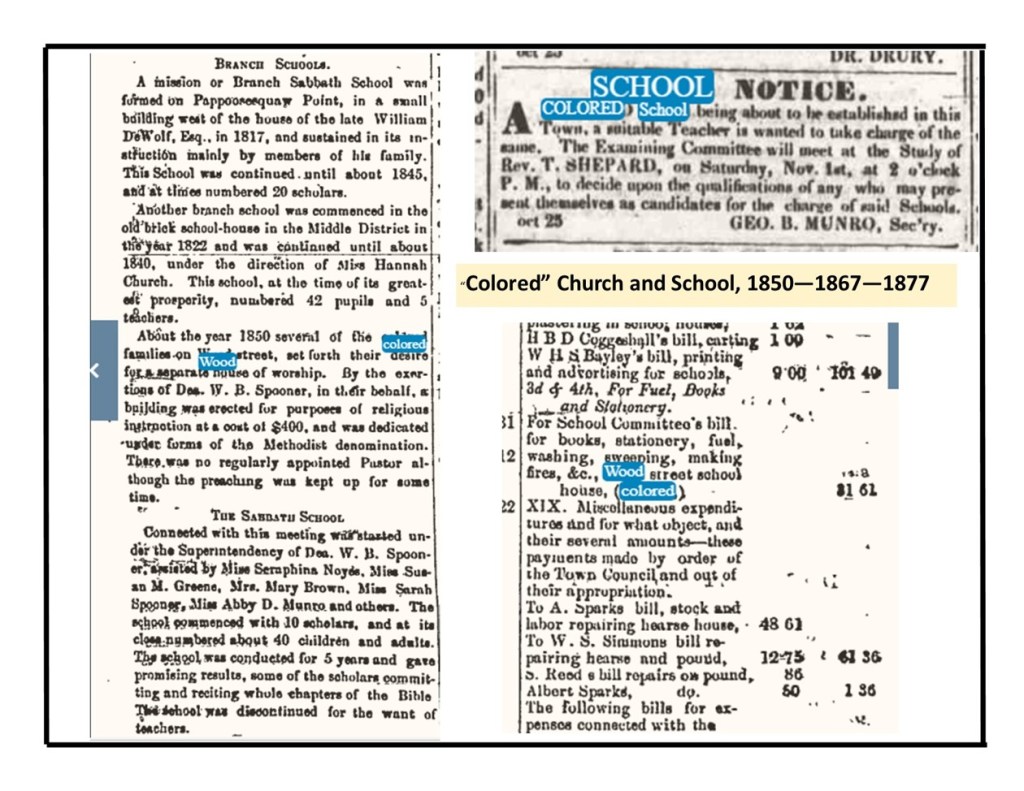

The map also marks the presence of an AME Church and school for the neighborhood children. Research on the land underneath the AME Church led us to a leaseholder named William H. Munro.

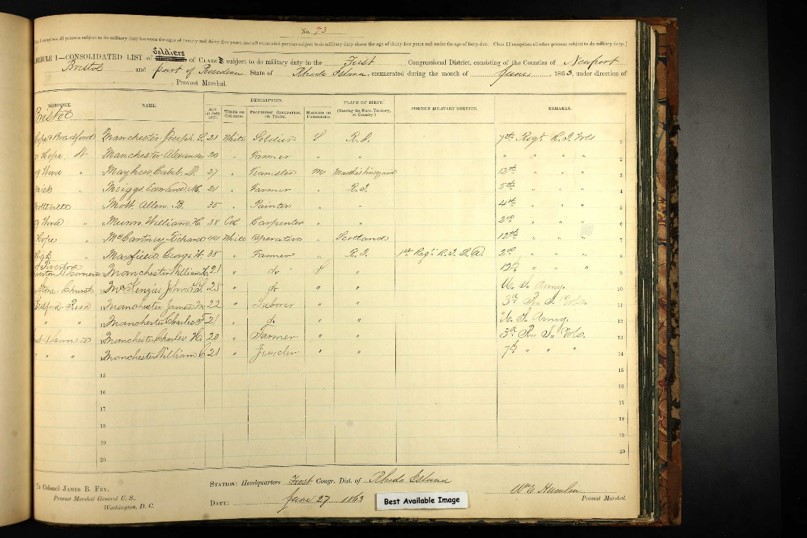

William H. Munro was a carpenter who served in the Civil War. You see here his enlistment papers; during various Civil War campaigns he was a wagoner with a six mule team under Gen Frank Wheaton. His obituary describes his Pokanoket heritage as a descendant of Chief Annawam, a captain under Sachem Massasoit.

Inn the 1850 census Munro is identified as mulatto, on this draft card he is identified as colored, in the 1880 census he is listed as white.

This building is on the site where the AME Church stood until the late 1880s. In an article in the Bristol Phoenix in 1890 it was reported “the small building, for many years located on the west side of Wood street, beween Bradford and Congregational, known as the A.M.E. Church, has been removed to Munro Avenue” (close to Lincoln Avenue). In June of 1890 the Phoenix reported that at the New England Annual Conference of the A.M.E. Church held in Worcester, MA, Rev. John Brown was appointed to the pastoral charge of the mission in Bristol. Research is ongoing.