Orville and Wilbur Wright. The Wright Flyer. Kitty Hawk December, 1903. The first sustained and controlled flight of a heavier than air flying machine. Made possible because of the years of work the brothers devoted while working in their Dayton, Ohio shop filled with printing presses, motors, and bicycles. Many years later, that bicycle shop was moved to Henry Ford’s Living Museum, Greenfield Village, just outside of Detroit. One of their bicycles is on display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

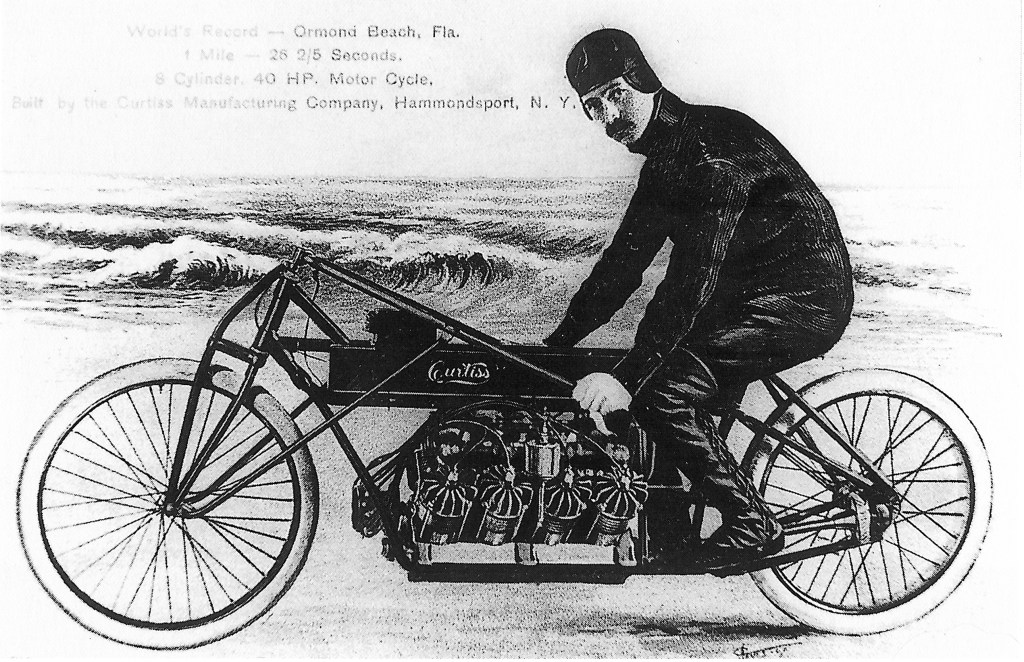

Another man, less famous, but also fascinated with flying, was Glenn Curtiss of New York (1878-1930). His career started with racing bicycles and motorcycles. In 1907 he set an unofficial world speed record of just over 136 mph on a 40 horsepower V-8 powered motorcycle that he designed. That record was not broken until 1930. Curtiss is credited with designing the handlebar throttle. More importantly, his powerful, but light, engines were much in demand for a variety of uses. [1]

After their flight in Kitty Hawk, the Wrights were very cautious about too much publicity as they very methodically went about securing as many patents on anything even vaguely aeronautical. Some observers even scoffed that they were so secretive that they chose a bland gray color for the cloth of their airplane wings so that the machine would blend almost invisibly into the sky when photographed. But by 1908 their flights became more “public”.

Partnering with Alexander Graham Bell, Glenn Curtiss and the Aerial Experiment Association focused on the design and build of their new air machine – christened the June Bug. The cloth on its wings was bright yellow. On July 4, 1908, Curtiss flew his June Bug 200 feet in the air, at 30 miles an hour, and for a distance of 5,080 feet over the fields and lakes of Hammondsport, New York. He won a $1500 prize offered by Scientific American. The contest committee from the Aero Club of America awarded Curtiss the nation’s first-ever pilot’s license. (Wilbur Wright would receive #5, as they were issued in alphabetical order.)

In September of that year, in Virginia, at a display for the U.S. Army, Orville flew with Lt. Selfridge on board as a passenger. Sadly, the plane crashed, and Tom Selfridge was killed. Nevertheless, 1908 is often called the miracle year for the airplane: the obstacles to powered flight had been overcome. “And almost all at once an assortment of airplane designs had begun to appear in Europe – primarily in France – with dozens of daring and glamorous aviators taking to the skies.”[2]

Samuel Pomeroy Colt no doubt kept a sharp eye on the advancement of aviation production. He saw a new market for his United States Rubber Company products in addition to his sales to the burgeoning automobile industry. Longacres, in New York City – known today as Times Square – had developed as the center of the carriage industry in the mid 19th century…….and by 1910 at least 75 automobile businesses had offices on Broadway just north of 42nd Street up to 59th Street.

“In 1911, the U.S. Rubber Company, a major tire company needing a presence in this automobile center, bought a plot at the southeast corner of 58th Street and Broadway and commissioned as architects Carrere & Hastings, then just finishing their monumental building for the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue at 42nd Street………U.S. Rubber rented out the 2nd to 13th floors (out of 20 total) but kept the ground floor as a tire showcase and the upper floors for its own offices.”[3]

So it is not unwarranted to assume that Samuel P. Colt was dazzled – as were thousands of New Yorkers – when Mr. Curtiss landed his Albany Flier (outfitted with pontoons and tires) in Manhattan at the end of a 150 mile flight from Albany, New York. Curtiss had sent a formal announcement of his intentions to the New York World – “I have made exhaustive experiments with the object of perfecting a machine that would start from and alight on the water.”[4] And so, the test flight, following the Hudson River, was completed – after, of course, a celebratory circle around the Statue of Liberty. This 152 mile success would change the world of aviation forever. “In one dramatic journey, Curtiss forges a path for the development of airmail, modern air travel, and the terrible prospect of air power in war.”[5]

Samuel P. Colt was busy building in Bristol, as well. In the early 1900s his “Casino”, or little house, is built on the farm, as well as an elaborate stone barn. Work is done on a seawall, and a stone bridge and entryway is graced with statuary from Europe, 5 of bronze, 7 of white stone, including the Kneeling Cupid, Venus, Apollo, Maiden from the Bath, Diana, two Wild Boars, The Gladiator – and the “Neapolitan Children” – one with a frog, one with a tortoise.[6]

So, in October of 1915 the two worlds merged: the beauty of the farm, and the excitement of hydroplanes.

“The exhibition given by Jack McGee of Pawtucket with his hydro-aeroplane last Sunday afternoon at Bristol, when, upon the invitation of Col. Samuel Pomeroy Colt, the aviator gave a demonstration of the workings of his pontoon-equipped flying machine, both on the water and in the air, for the entertainment of a party of guests of Col. Colt, has been one of the most talked about happenings in social and other circles during the past week.”[7]

The article goes on to say that a half a hundred guests were entertained, and although the event was “out of the ordinary”, it was very much in keeping with Col. Colt’s reputation as a host and entertainer. Townspeople of Bristol and across the state were invited as spectators, and nearly a thousand gathered, with many Connecticut and Massachusetts issued license plates on the parked automobiles reported.

After the aviator did a few demonstration spins around the property, he took six guests, one at a time, up for a ride. Mrs. William Beresford of Providence was the first – followed by Mrs. Philip DeWolf, then Mr. Beresford, and finally Col. Colt’s driver Floyd Heustis and his butler Clover Miller. One woman from the crowd was the final passenger, but the reporter for the Providence Tribune did not capture her name. The highest altitude reached was about 350 feet, the distance was about 8 miles, and each flight took around 13 minutes. “Mrs. Beresford alighted from the machine none the worse for the trip; in fact, she was very enthusiastic about its novelty and its delights.”[8]

The Colonel’s special guests then enjoyed a luncheon served in the Casino and in the Mauran Cottage, with live music provided by the Crown Orchestra. Mr. McGee and his hydroplane remained overnight and he departed at 10 o’clock in the morning on Monday.

The Colonel was congratulated on “providing his guests much to instruct and at the same time much of benefit in the familiarization with aeroplanes which are now so prominent in the great European war.”[9]

A map, undated, provided by the State of Rhode Island Division of parks and Recreation show the location of various buildings – including a notation of “Site:Airstrip”.

Colonel Colt leased shore rights on the Colt Farm, Poppasquash, “at the foot of the Asylum Road, just north of the oyster watchman’s house, and commonly known as the Asylum Shore” to the Curtiss Aeroplane Company of New England. An Aerodrome was built, 35 feet by 85 feet, capable of housing at least two planes. The plan of the Curtiss Company was to provide regular air taxi service “between all points within telephone connection of Bristol and Buzzards Bay”. The terminal was named the “Thomas Base for Seaplanes”, in honor of Reginald D. Thomas of Waltham, Massachusetts, “one of the expert seaplane pilots developed by the United States Navy during the war”. Six seaplane bases were established by Curtiss and associated companies – among those were locations at Rutland, VT, Old Orchard Beach, ME, and Taunton, MA.

Eventually, commissioned by the U.S. Navy in 1917, it was a Curtiss NC-4 that was the first aircraft to fly across the Atlantic in 1919, crossing via the Azores. Curtiss built four plans—NC-1, NC-2, NC-3, and NC4-—the “Nancies” – but only the NC-4 made it. Perhaps it was blessed by the hull that was designed and built by the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company of Bristol. Hull number 341 eventually became the NC-4 . NC-4 is on display in Pensacola, Florida in the National Museum of Naval Aviation. In 2019 a presentation on the NC-4 was given at the Herreshoff Museum, and you can click on this link to watch that presentation: https://herreshoff.org/2020/04/hull341/

In 1921, the story of the seaplanes soaring over Bristol takes a sharp turn.

According to the Bristol Phoenix of August 9, 1921, a “tiny” motorboat at anchor just off Hope Island came under attack. “A swift gray seaplane with the machine gun at its bow rippling the surface of Narragansett Bay with a rain of bullets” strafed the small boat. A bullet hit Miss Grace Buxton in the leg. Frank Toole of Providence and William Oakes of Connecticut “tore their clothing into strips to bind the wounds”. Her other companions, frantically bailing water out of the board due to the numerous holes in the hull, made it to the wharf at Bullneck Cove, Oakland Beach, and a doctor was called. Luckily, the bullet passed through Miss Buxton’s right calf and grazed the flesh of the left. She did eventually make a full recovery. United States Senator LeBaron Colt (brother of Samuel P. Colt) ordered a full military inquiry into the incident. Seaplane #92 was piloted by Lt. Edward T. Garvey. 5 crew were also aboard. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt III made a strong statement that there were rigid instructions in place designed to protect civilians where naval aircraft were operating.

Lt. Garvey was ordered before a general court martial on charges of neglect of duty in failing to take customary precautions.

On October 20, 1921 it was announced by Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby that Lt. Garvey was found not guilty. (Historical note: Denby was later implicated in the Teapot Dome scandal of the Warren Harding Presidency).

The investigation revealed that mechanical failure caused the forward gun to jam in an operating position, during their target practice. Miss Buxton seemed to take it all in stride. “I know now how the boys in the war felt when fired upon from the air.”

Samuel Pomeroy Colt died at his Bristol home, Linden Place, in August of 1921. Glenn Curtiss and his family had moved to Florida in the 1920s, and he died on July 23, 1930. By an Act of Congress in 1933 Curtiss was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

By 1929, twelve aviation-focused companies, including Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company and Wright Aeronautical, joined to form the Curtiss—Wright Corporation, still in business today. Headquartered in Davidson, NC, their net sales were $2.4 billion in 2020.

Today when you ride on an airplane and look out the window and see the flaps in the wings extend out, thank Glenn Curtiss for the invention of the aileron. And when you enjoy Colt State Park on a warm summer day, look up into the blue skies ……. and think about Josephine and her flying machine:

Come Josephine in my flying machine,

Going up she goes! Up she goes!

Balance yourself like a bird on a beam

In the air she goes! There she goes!

Up, up, a little bit higher

Oh! My! The moon is on fire

Come Josephine in my flying machine

Going up, all on, Goodbye!

The song Come Josephine in My Flying Machine (Up She Goes!) was written by Fred Fisher and Al Bryan and was first recorded by Harry Tally in 1911.

Epilogue:

I contacted the Curator of the Curtiss Museum in /Hammondsport, NY to see if their files contained any information on the aerodrome on the Colt Farm in Bristol. Curator Rick Leisenring was kind enough to write, “By 1916 the Curtiss group of companies (Motor Co., Aeroplane Co., Engineering Co., Exhibition Co., flying schools) had been consolidated under the Curtiss Aeroplane & Motor Corp. with Glenn at the head. His personal involvement in much of the corporation’s dealings diminished and in 1918 he retired from aviation all together. He immediately began developing land in Florida, founding the cities of Hialeah, Opa-Locka and Miami Springs. He also went into the travel trailer business with the Adams Motor Bungalo Co. followed by the Curtiss Aerocar Corp. I have not found any references to Glenn personally dealing with the (Colt) project.”

[1] Shulman, Seth, page 189

[2] Ibid, page 145

[3] New York Times November 26, 1989 “Restoring Lustre to a 1912 Lady.”

[4] Shulman, Seth, page 189

[5] Ibid, page 201

[6] Providence Journal, May 20, 1906

[7] Providence Evening Tribune, October 31, 1915

[8] Ibid

[9] Ibid